TLDR:

- India’s leap: Maruti Suzuki’s first born-EV, the e-Vitara, rolls out of Gujarat for export to 100+ countries, backed by a ₹70,000 crore commitment and a new battery electrode plant.

- Cracks in the story: dependence on imported minerals, supplier gaps, and the challenge of meeting strict EU/Japan standards could slow the export playbook.

- Next chapter: Gujarat as ground zero for India’s EV export push, tying into Japan’s $68B investment plan and a massive skilling programme to make India a global EV hub.

The Bite:

On August 26, 2025, Prime Minister Narendra Modi flagged off the e-Vitara; Maruti Suzuki’s first born-electric vehicle, from the company’s plant in Hansalpur, Gujarat.

It had all the usual elements of a big launch: cameras, speeches, and a clean mobility backdrop. But this wasn’t just about starting production on a new car.

The e-Vitara marks a quiet but important shift in India’s EV journey. It’s the first electric vehicle from Maruti Suzuki built entirely on a dedicated EV platform with no ICE (Internal Combustion Engine).

ICE is basically a traditional petrol or diesel-powered engine where fuel is burned internally to generate power.

And it’s not just for Indian roads. Starting this month, the e-Vitara will be exported to over 100 countries, including Europe, the UK, and Japan.

That last bit is worth pausing on.

You’re not wrong to think this feels like a full-circle moment. Japan gave India its first Maruti back in the 80s. Now India is returning the favour, exporting electric Suzukis back to Japan. In global trade terms, that’s like a student handing back the teacher’s textbook, with a few chapters rewritten

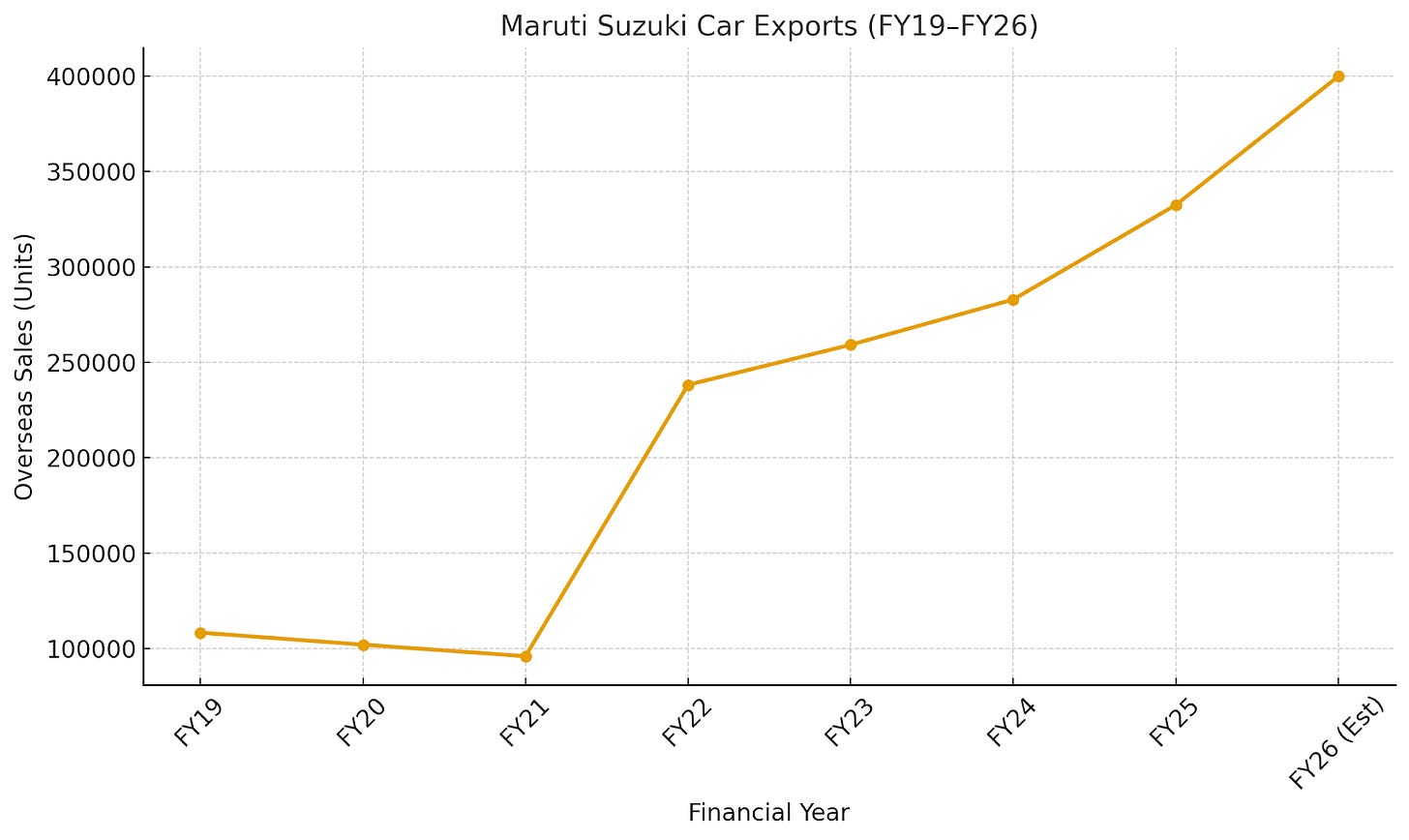

Speaking at Hansalpur, PM Modi noted, “For the past four years, Maruti Suzuki has been the largest exporter of cars from India.” The focus is no longer just on assembling vehicles. It’s about building EVs in India that can be sold globally.

But why is this such a big deal? And why does it matter to someone who’s not buying an SUV this year?

Let’s start with the scale.

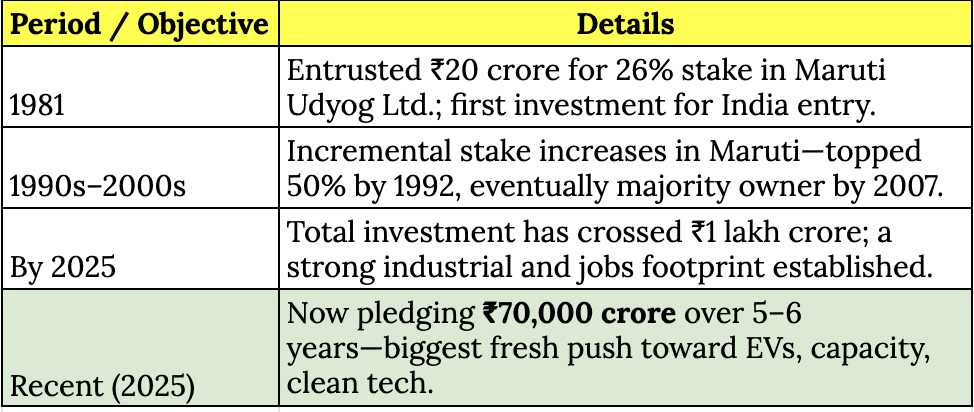

Suzuki, through its India arm, has committed ₹70,000 crore, that’s $8.5 billion over the next five to six years. A massive chunk of that is going into Gujarat’s Hansalpur plant, where the e-Vitara is being made. This plant will eventually roll out a million vehicles a year, making it one of the largest auto manufacturing hubs in the world. And that’s not just for Indian buyers. The very first batch of e-Vitaras is already headed to Europe from Gujarat’s Pipavav Port.

Now think about what happens when India doesn’t just use EVs, but also exports them.

It changes how global automakers treat us. It changes who gets the tech first, who sets the price, and where the investment flows. You don’t get 100+ countries on your export list unless your product is globally compliant: safety, emissions, tech features, battery standards. And that’s what makes this launch different.

Because Suzuki didn’t just launch a car. It launched a platform.

The e-Vitara’s base, co-developed with Toyota and Daihatsu is a fresh EV-only design. It’s modular. It’s export-ready. It’s also the base for Toyota’s upcoming Urban Cruiser EV. That’s a signal. This isn’t India catching up. This is India hosting the party.

Of course, no Indian EV story is complete without one big question; what about the batteries?

Here’s where it gets even more interesting. Alongside the car, PM Modi also inaugurated a battery electrode manufacturing plant (basically the part of the battery that stores and releases energy) in the same Hansalpur complex. And this isn’t some token localisation effort. It’s a joint venture between Suzuki, Toshiba, and Denso and it’s the first in India to manufacture lithium-ion battery electrodes (both anodes and cathodes) at scale.

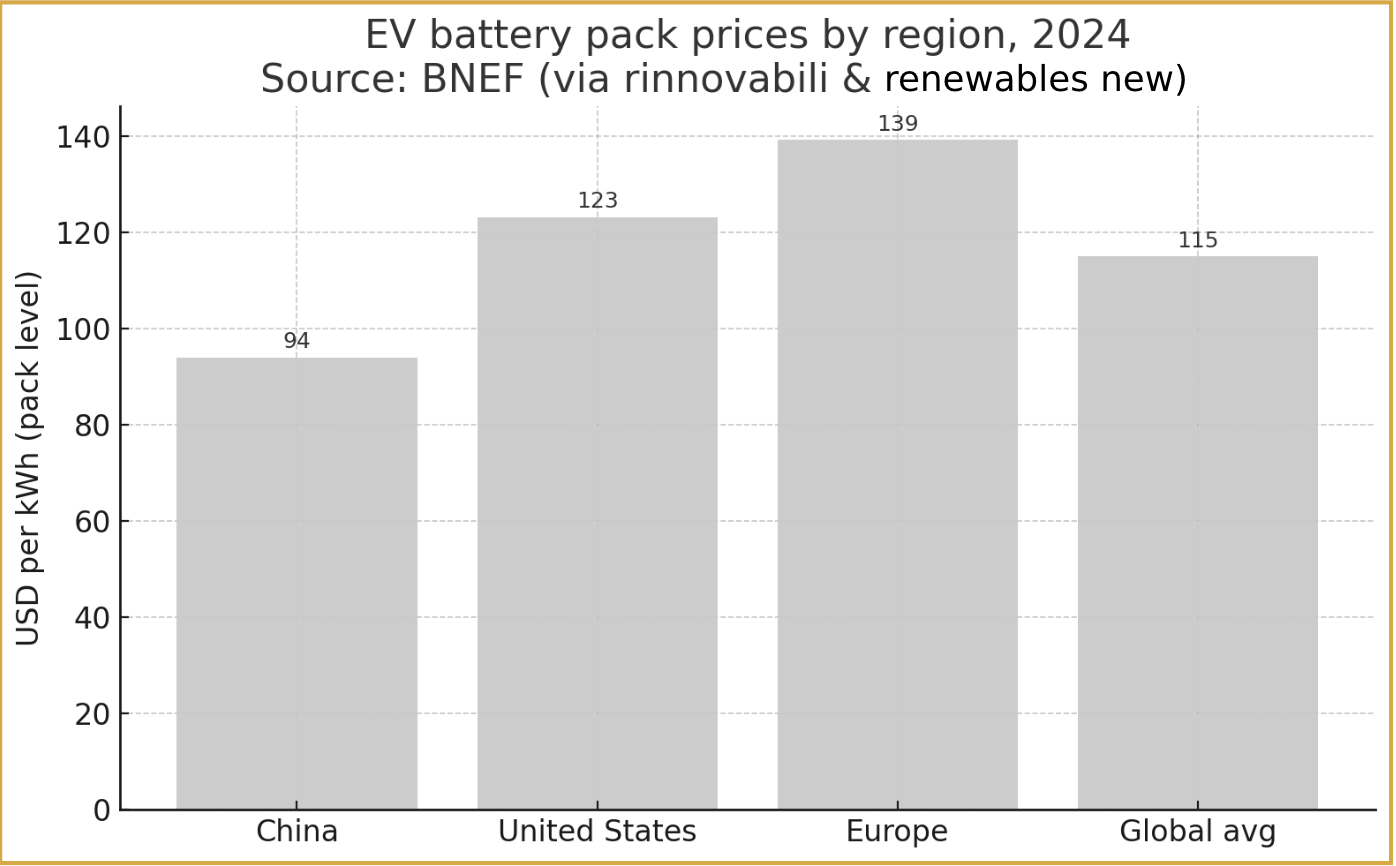

That’s a big deal. Until now, even if batteries were assembled in India, the core components came from China or Korea.

The government knew this.

Which is why the PM officially linked the Hansalpur electrode plant to India’s broader Critical Minerals Mission; the national push to secure supplies of lithium, cobalt, nickel, and other key battery metals.

Because battery electrodes aren’t just about manufacturing, they rely on hard-to-source materials like lithium, cobalt, nickel, and graphite. And right now, most of those come from outside India, often from regions with complex geopolitics. China, for instance, has used its dominance in battery-grade inputs and rare earths as leverage more than once. The moment exports get restricted, the global EV supply chain feels the heat.

India is already taking steps to secure those critical minerals. The Geological Survey of India is exploring more than 1,200 sites across Rajasthan, Odisha, and the Northeast, hoping to build a domestic supply base.

The aim is clear: reduce dependence on imports and capture more of the EV value chain.

This is what makes Hansalpur more than just another factory. It signals India’s shift from being an EV assembler to becoming a deeper player in the ecosystem, not just making cars, but anchoring the supply chain around them.

An aerial view of Maruti Suzuki's stockyard in Gujarat, displaying only about 2-3% of its annual production. The plant produces 7.5 lakh cars every year.

Because at the end of the day, most of an EV’s cost comes from the battery, and most of a battery’s cost comes from the materials (Lithium, Nickel, Cobalt, Manganese, Iron, Aluminun etc) inside it. Which means the story doesn’t stop in Gujarat. It extends to mineral-rich regions across the world and India is now putting money on the table.

The government has reportedly finalised a $600 million investment for a 20% stake in SQM’s lithium mines in Western Australia, known for some of the most reliable, long-life lithium reserves globally. That deal alone could give India a decade of assured access to battery-grade raw material.

But for now, dependence on imports remains high. Nickel and cobalt, in particular, still come largely from China and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Experts say imported materials account for nearly 60% of India’s battery cost today. That’s why Hansalpur’s electrode plant is important; it won’t remove dependence overnight, but it will slowly chip away at it, reducing costs and building capability over time.

So what does all this mean for Gujarat?

Gujarat is now ground zero for India’s EV export strategy. The e-Vitara and electrode plants are expected to create thousands of direct jobs and many more indirect ones across logistics, chemicals, electronics, and MSMEs. Infra investments worth over ₹1,000 crore are already underway in power and logistics around the plant.

And when a region starts exporting EVs to Europe and Japan, guess what happens next? Ancillary industries, from auto components to charging tech and AI-based quality systems, all move closer to the action.

Here’s the real test: every nut, wire, and circuit that goes into the e-Vitara must now meet EU, UK, and Japanese quality and ESG standards. That’s where India’s challenge begins.

While some supplier hubs in Pune, Hosur, and Surat are moving fast, many tier-2/3 vendors are still lagging behind; struggling with Six Sigma quality, carbon audits, e-invoicing systems, and global certifications.

There’s also a tech skills gap. Components like battery-grade ceramics, power electronics, and safety systems are still import-heavy. Without serious R&D or shared testing infrastructure, many MSMEs may get left out of the export race.

Suzuki is handholding some of them with training and audits. But time’s ticking. India needs to scale support infra, fast.

Some estimates suggest Gujarat’s GSDP could grow 0.5–1% annually just from the ripple effects of this EV ecosystem. And the math adds up. EVs are capital-heavy, export-ready, and value-dense. Unlike textiles or basic chemicals, every step of the EV supply chain comes with high multiplier effects from mining and processing to software and services.

And once you start looking at supply chains, you can’t ignore geopolitics

The China pivot is real with rising costs, trade tensions, and supply chain risks having pushed global players to look elsewhere. Japan, the US, and Europe all want to diversify. And India, with its large market, strategic location, and skilled labour, is a serious alternative. That’s why Japan is putting money into battery cells and semiconductors here. That’s why Suzuki is turning India into its export base.

Just days after the e-Vitara event, PM Modi landed in Tokyo for the India–Japan Annual Summit (Aug 29–30, 2025). EVs weren’t formally on the agenda but everything about the summit reinforced what Hansalpur stood for.

Modi and Japan’s PM Shigeru Ishiba announced a 10-year “Vision Plan” to deepen ties in clean energy, semiconductors, defence tech, rare-earths, and industrial capacity. They also announced a ¥10 trillion (~$68 billion) private investment roadmap into India.

An Economic Security Initiative was launched for a supply-chain resilience plan across five strategic sectors, including EV inputs and advanced materials.

The message was unmistakable: Make in India, for the world with Japanese capital, tech, and global market access.

To power all this, Suzuki knows factories aren’t enough. You need people trained in EVs, people who can build and fix high-voltage systems.

Maruti Suzuki to conduct High Voltage Training across 130 ITIs in India.

That’s why, it launched a massive EV-focused training initiative across 130+ Industrial Training Institutes (ITIs) in 24 states and 4 union territories. Starting September 2025, over 4,100 students each year will graduate with skills in:

- Battery diagnostics and repair

- EV architecture and safety

- Charging systems and grid interfaces

The curriculum is co-developed with Japanese partners, making it one of the largest EV skilling programmes in India’s auto history.

Of course, India still has its growing pains. Infra gaps, compliance friction, and policy unpredictability remain real concerns. Battery materials still cost 20–30% more to make here than in China. And while labour costs are low, building a workforce skilled in EV technologies will take sustained investment in training something Suzuki has only just begun addressing through its new skilling programme.

So if you’re Japan, this move is strategic: diversify, hedge your bets, build with a democratic partner. But it’s also a gamble. If production slips, if compliance bites, or if costs stay stubbornly high, the export playbook could unravel. And Japanese automakers don’t do well with surprises.

But if India delivers and Suzuki clearly believes it will, this could be the beginning of something much bigger. Bigger than Maruti. Bigger than EVs. We’re talking about India as the next East Asian-style platform economy for clean mobility, built for global distribution.

The ripple effects extend beyond Suzuki’s plant, right into its supplier network.

This battery facility isn’t just about what Suzuki builds; it’s about what everyone around Suzuki now needs to supply. Anode-grade graphite, battery chemicals, high-precision equipment, even AI-driven monitoring software; none of this was produced at scale in India. Now it has to be.

Local players are already stepping in. Companies like Epsilon Advanced Materials, Himadri Speciality Chemicals, and HEG are eyeing the space, while specialty chem and pharma firms are testing the waters. Even startups are experimenting with AI systems to manage electrode production in real time. That’s how new industries take root.

The impact doesn’t stop at suppliers either.

Every e-Vitara exported begins its journey from Pipavav Port, about 250 km from Hansalpur. Suzuki has set up a dedicated logistics corridor with cold storage for batteries and ISO-grade EV containers to handle exports. But moving cars at global scale need more than ports; it needs reliable roads, power, and uptime. Following that, Gujarat has committed over ₹1,000 crore to upgrades in high-voltage lines, water systems, and rail connectivity.

Charging infra is also inching forward. Big cities are adding public chargers, while Tier-2/3 towns and highways still lag behind. Initiatives like Tata EV Mitra and PM e-DRIVE are filling gaps, but coverage is patchy.

Meanwhile, investors are taking notice. On launch day, Maruti Suzuki’s stock rose 1.7%, reflecting optimism about exports. Analysts expect more than 67,000 e-Vitaras to ship by March 2026, largely to Europe. That’s not a test run. That’s scale.

And remember, EVs still make up less than 5% of India’s car market. In other words, the home market is just getting started. This launch is as much about exports as it is about India.

So yes, the e-Vitara photo may look like just another ceremonial moment. But it’s more than that. It’s like pouring lithium into India’s industrial bloodstream. It’s an electric car, yes, but also a signal to global investors, local suppliers, and anyone who still thought India was only playing catch-up in clean tech.

And if that signal holds, then Gujarat’s EV highway just got a turbocharged lane.

If you’ve made it this far, thanks for reading. We’ll be back next week, like clockwork.

Got a company, sector, or story you think we should dig into? Hit reply and tell us.

If we pick your suggestion, we’ll send some Filter Coffee merch your way.

Coffee Crew out.